Scrooge is a bitter old man who loves his money and hates Christmas. But everything changes when he is visited by three ghosts.

A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens.

This story has been rewritten in modern English so that English learners can enjoy it.

Chapter 1

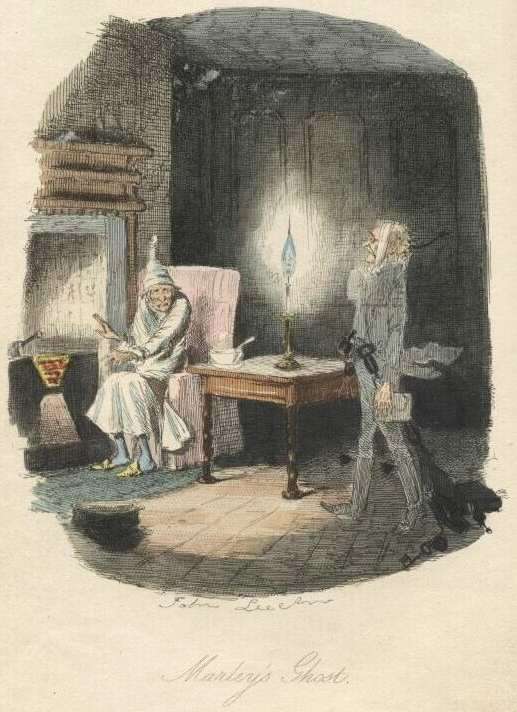

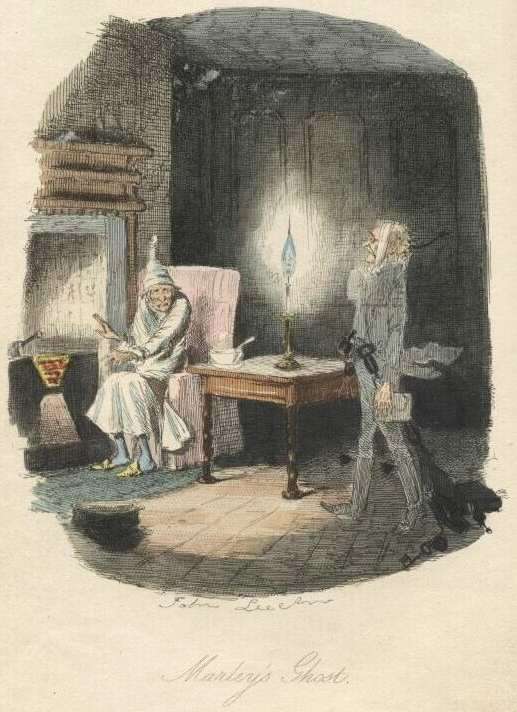

Marley’s Ghost

Marley was dead. There is no doubt about that.

His death was registered and signed by a priest, an officer, a mortician, and a mourner. Scrooge signed it. Scrooge’s signature made it official. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.

As dead as a doornail. Isn’t that a strange English expression. Why do we compare death to doornails? Of all the nails in the world, wouldn’t a coffin nail be the deadest? Why don’t we say, as dead as a coffin nail?

Well, whatever the expression is, Marley was dead. As dead as a doornail.

Did Scrooge know that he was dead? Of course he knew. How could he not know? Scrooge and Marley were partners for… well, I don’t know how many years. They were partners for a long time.

Scrooge was the only person that Marley worked with, the only one he asked for advice, the only one he wrote in his will, the only one he was friends with. And, Scrooge was the only one who attended Marley’s funeral.

Even so, Scrooge was not terribly sad about it. He took care of the funeral arrangements in a business-like manner.

Now, I must say this again: Marley was dead. Marley was dead and there is no doubt about it. If you don’t understand this, the story can not continue.

Scrooge never erased Marley’s name from his door. Even years later, the warehouse door said: Scrooge and Marley.

Their company was known as “Scrooge and Marley.” Sometimes, new customers called him “Scrooge,” and sometimes they called him “Marley.” Scrooge answered to both names. It was all the same to him.

But Scrooge was skilled at his job. What was his job? He was a loan shark. He loaned money to people who needed cash, and then he made a profit by charging a high interest.

Scrooge was not a likeable person. He always seemed unaffected by the weather. No summer could warm him, and no winter could chill him. No wind was more bitter than him. No rain drop was more stubborn than him.

Nobody ever stopped him on the street to say, “Hello, Scrooge! How are you? I haven’t seen you in a while.” No beggars asked him if he could spare some coins. No children asked him what time it was. No man or woman, ever, asked him for directions. Even dogs seemed to know him; when they saw him coming, they would tug their owners in a different direction.

But Scrooge didn’t care! In fact, he liked it. It seemed like wherever Scrooge went, all creatures kept their distance.

Now, this story starts on Christmas Eve. Yes! Of all the days of the year, we start on Christmas Eve.

On Christmas Eve, old Scrooge was sitting alone in his office, counting money. It was cold, biting weather. It was even foggy. He could hear the people walking by. He could hear them stamping their feet and beating their hands to stay warm. The church clock had struck three o’clock, but it was already quite dark. All day, it had been rather dark because of the weather. The neighboring offices had candles burning in the windows.

The door of the office was open so that he could keep an eye on his clerk, who was copying letters in a small room that looked like a prison cell. Scrooge had a small fire in the office, but the clerk’s fire was so small that it looked like it had only one coal. But the clerk couldn’t replenish it because Scrooge kept the coal box in his own room. The poor man put a blanket over his shoulders and pulled a candle closer.

“Merry Christmas, uncle! God bless you!” cried a cheerful voice. It was the voice of Scrooge’s nephew, who came up behind him suddenly.

“Bah!” said Scrooge, “Humbug!”

Scrooge’s nephew had warmed himself up by walking rapidly through the winter weather. This made his face glow. He was cheerful and handsome, and his eyes sparkled. Warm breath came out like smoke.

“Don’t say humbug to Christmas, uncle!” said Scrooge’s nephew. “You don’t mean that, do you?”

“I do,” said Scrooge. “Merry Christmas! And what right do you have to be merry? What reason is there to be merry? You are poor enough.”

“Come on,” returned the nephew brightly. “What right do you have to be grumpy? What reason is there to be morose? You are rich enough.”

“Humbug.”

“Don’t be angry, uncle!”

“What else can I be,” said Scrooge, “when I live in such a world of fools? Merry Christmas! Who needs a merry Christmas! What’s Christmas to you? It’s just a time for paying bills. A time for finding out that you’re a year older. A time for checking your finances. A time for calculating your year’s spending and profits.”

“Every idiot,” Scrooge continued, “who says ‘Merry Christmas’ should be thrown into a pot of boiling pudding, and then buried with a Christmas tree branch stabbed through his heart. That’s what I think!”

“Uncle!” pleaded the nephew.

“Nephew!” returned the uncle sternly, “celebrate Christmas in your own way, and let me celebrate it in mine.”

“Celebrate it!” repeated Scrooge’s nephew. “But you don’t celebrate it.”

“Let me leave it alone, then,” said Scrooge. “Christmas won’t do anything good for you. And it hasn’t done anything good for you!”

“I have seen many good things that come from Christmas. It’s not only about profits, I dare say,” said the nephew. “It’s about being kind, forgiving, charitable and pleasant. It’s the only time of the whole year when men and women open their hearts freely. Instead of looking at other people like they are creatures on separate journeys, we look at other people like they are fellow passengers in the journey of life. And no, uncle, it has never put a piece of gold or silver in my pocket, but I believe that it has done good for me. And it will continue do good for me. God bless it!”

The clerk in the cell involuntarily clapped his hands in applause. Almost immediately, he realized his rude actions. He poked the fire, and extinguished the last frail spark.

“Don’t let me hear another sound from you,” said Scrooge to the clerk, “or I’ll fire you so you can celebrate Christmas at home!” He turned to his nephew and added, “You’re quite a powerful speaker, sir. I wonder why you don’t get a job in the Parliament.”

“Don’t be angry, uncle. Come! Have dinner with us tomorrow.”

Scrooge rejected the offer.

“But why?” cried Scrooge’s nephew. “Why?”

“Why did you get married?” asked Scrooge.

“Because I fell in love.”

“Because you fell in love!” growled Scrooge, as if that were the only thing in the world more ridiculous than a merry Christmas. “Good night!”

“Uncle, you can’t say that you won’t visit me because I’m married. You never came to visit me even before I was married. What’s the real reason?”

“Good night,” said Scrooge.

“I don’t want anything from you. I’m not asking for anything. Why can’t we be friends?”

“Good night,” said Scrooge.

“I’m sorry, with all my heart, that you are so stubborn. We have never had any fight before. But I have come here in the spirit of Christmas, and I’ll keep my Christmas spirit until the end. So, I wish you Merry Christmas, uncle!”

“Good night,” said Scrooge.

“And A Happy New Year!”

“Good night,” said Scrooge.

His nephew left without an angry word. He stopped for a moment to give a seasonal greeting to the clerk. As cold as the clerk was, his heart was warmer than Scrooge’s, and he returned the greeting cheerfully.

“There’s another fool,” muttered Scrooge, who overheard them, “my clerk, making fifteen shillings a week, with a wife and family, talking about a merry Christmas. Absolutely absurd.”

As Scrooge’s nephew left, two other people came in. They were portly gentlemen with a pleasant demeanor. They took their hats off and stood in Scrooge’s office. They had books and papers in their hands.

“This is Scrooge and Marley’s, I believe,” said one of the gentlemen, referring to his list. “Do I have the pleasure of talking to Mr. Scrooge, or Mr. Marley?”

“Mr. Marley has been dead for seven years,” Scrooge replied. “He died seven years ago, this very night.”

“We have no doubt his generosity is well represented by his surviving partner,” said the gentleman, presenting some papers.

At the ominous word “generosity,” Scrooge frowned, and shook his head.

“At this festive time of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking out a pen, “it is more gratifying than usual to donate to the poor, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands of people need common goods; and hundreds of thousands would like common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“They are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “unfortunately.”

“The prisons and the workhouses are very active?” said Scrooge.

“Both very busy, sir.”

“Oh! From what you said, I was afraid that something had happened to them,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear that they are still being useful.”

“We would like to spread Christian cheer to these poor people,” returned the gentleman, “so we are raising funds to buy them some meat and drinks, and coal for their fires. We raise money during Christmas time because this is the time when the poor feel their suffering the most. How much shall I write down that you donated today?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to donate anonymously?”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that is my answer. I don’t make myself merry at Christmas, and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I support the prisons and the workhouses.”

“But there are many who can’t go to the workhouses. And there are many who would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “then they had better do it. It will decrease the surplus population. Good night, gentlemen!”

Seeing that it was useless to argue, the gentlemen gave up and left. Scrooge resumed his work, thinking highly of himself.

Meanwhile, the fog and darkness thickened. Horses and carriages were on their way up and down the streets. The ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping down at Scrooge out of a Gothic window, became invisible. When the bell struck the hour it sounded like teeth chattering through the fog.

The cold became intense. In the main street, at the corner of the court, some workers were repairing the gas pipes. They had lighted a fire, and a party of ragged men and boys gathered around it, warming their hands and blinking their eyes in front of the happy blaze.

The shop windows were bright, and the holly sprigs and berries crackled in the lamp light. Butchers and grocers were cheerful as customers crowded their shops.

The Lord Mayor, in his mighty Mansion House, gave orders to his fifty cooks and butlers to celebrate Christmas as a Lord Mayor’s household should. Even the tailor, whom the Lord Mayor had fined five shillings the previous Monday for being drunk in the streets, made pudding while his wife and baby went out to buy beef.

It became even foggier and colder. It was a piercing, biting cold.

A young man, shivering in the cold, stopped at Scrooge’s doorstep to sing a Christmas carol. But at the first line of,

“God bless you, merry gentleman,

May nothing you dismay,”

Scrooge threw open the door with such energy that the singer fled in terror.

Finally, it was time to close up the shop. Scrooge dismounted from his stool, and he tacitly mentioned that it was closing time to his clerk, who instantly blew out his candle and put on his hat.

“You’ll want all day off tomorrow, I suppose?” said Scrooge.

“If it’s convenient, sir.”

“It’s not convenient,” said Scrooge, “and it’s not fair. If I was to stop paying you, you’d think it was unfair, wouldn’t you?”

The clerk smiled faintly.

“And yet,” said Scrooge, “you don’t think it’s unfair for me when I pay you a day’s wages for no work.”

The clerk said that it was only once a year.

“It’s a poor excuse for picking my pocket every twenty-fifth of December!” said Scrooge, buttoning his great coat up to his chin. “But I suppose you must have the whole day off. Be here extra early the next morning.”

The clerk promised that he would, and Scrooge walked out with a growl. The office was closed, and the clerk, with his white blanket over his shoulders (because he didn’t have a winter coat), ran home to Camden Town as fast as he could.

Scrooge ate his melancholy dinner in his usual melancholy tavern. He read all the newspapers, checked his bank book, and then went home to bed.

He lived in an old house which had once belonged to his deceased partner. It was a gloomy set of rooms with a lonely yard. There were no other buildings around it, as if someone had dropped off a house there and forgotten about it.

Scrooge was the only one living there, and all the extra rooms were rented out as offices. The fog and frost hung around the house. The yard was so dark that even Scrooge, who knew every stone of it, had to grope with his hands.

Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all special about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact that Scrooge had seen it, every morning and night, during his whole stay at that house. Also, keep in mind that Scrooge had not had a single thought about Marley since the afternoon conversation about his dead partner.

Knowing that, try to explain to me, if you can, why this happened:

Scrooge, putting his key into the lock of the door, looked at the knocker. And he saw, not the knocker, but Marley’s face.

Marley’s face.

It wasn’t in shadows like the other objects in the yard were. It had a dismal light around it, like a firefly in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but it looked at Scrooge like Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles resting on his ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously flowing, as if by someone’s breath or by wind. Though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. It was horrible.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it became a knocker again.

To say that he was not startled would be untrue. He felt strangely conscious of the blood flowing through his body. But he turned the key sturdily to open the door, walked in, and lighted his candle.

He did pause, for just a moment, before he shut the door. He did look cautiously behind it first, as if he half expected the sight of Marley’s pigtail sticking out the other side of the door. But there was nothing on the back of the door, except the nuts and screws that held the knocker on, so he said, “Pooh, pooh!” and closed it with a bang.

The slam of the door resounded through the house like thunder. Every room above, and every corner of the wine merchant’s cellars below, seemed to have a different way of echoing. Scrooge was not the type of man who was frightened by echoes. He locked the door, walked through the room, and up the stairs, slowly. He trimmed his candle before going up the stairs, and walked through the darkness.

Scrooge went up the stairs, not caring about the darkness. Darkness is cheap, and Scrooge liked it. But before he shut the heavy upstairs door, he walked through all his rooms to see that everything was right.

He checked the living room, bedrooms, and the storage room. They were all as they should be. There were no faces under the table, and nobody under the sofa.

There was a small fire in the fireplace, with a spoon and saucepan ready with gruel.

There was nobody under the bed. Nobody in the closet. Nobody wearing his robe, which was hanging up on the wall.

Quite satisfied, he closed the door and locked himself in his bedroom. He double locked himself in, which was not his custom.

Feeling secure, he took off his clothes and put on his robe, slippers and nightcap. He sat down in front of the fire to have his gruel.

It was a very low fire indeed, especially for such a bitter night. He had to sit close and lean over it before he could even feel its warmth.

The fireplace was an old one, built by a Dutch merchant long ago, and paved with quaint Dutch tiles that illustrated some religious scriptures. There were pictures of Cain and Abel, Pharaoh’s daughters, Queens of Sheba, Angelic messengers, Abraham, kings of Babylon and Apostles. There were many faces in the tiles that could have distracted Scrooge, but he could only think of Marley’s face.

“Humbug!” said Scrooge, and he walked across the room.

After pacing the room, he sat down again. As he threw his head back in the chair, his eyes happened to fall on a bell that hung in the room. It used to be used to communicate with the maids on the highest floor of the house.

With great astonishment, and with an inexplicable dread, he saw this bell begin to swing. It swung so softly that it scarcely made a sound, but soon, it rang out loudly, and so did every bell in the house.

This might have lasted for thirty seconds, or a minute, but it seemed like an hour. The bells ceased as suddenly as they had begun.

Following the bells was another clanking noise, deep down below, as if someone were dragging a heavy chain over barrels of the wine cellar. That’s when Scrooge remembered hearing that ghosts in haunted houses were described as dragging chains.

The cellar door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder on the floor below. And then coming up the stairs. And then coming straight towards his door.

“Humbug!” said Scrooge. “I won’t believe it.”

His color changed, though, when the noise came through the heavy door and passed into his room in front of his eyes. When it came in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, “I know him! Marley’s ghost!” and then fell again.

The same face. The very same face. Marley in his usual waistcoat, tights and boots, with his hair in a pigtail.

He was pulling a chain which was clasped around his middle. It was long, and fell behind him like a tail. It was made of cash boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, contracts, and heavy purses made of steel. His body was transparent, so Scrooge could see straight through to the inside of his waistcoat.

Scrooge looked at the phantom standing in front of him. He felt the chill of its deathly cold eyes.

“How now!” said Scrooge, as cold as ever. “What do you want with me?”

“Much!” It was Marley’s voice. There was no doubt about it.

“Who are you?”

“Ask me who I was.”

“Who were you then?” said Scrooge, raising his voice. “You’re particular, for a ghost.”

“In life I was your partner, Jacob Marley.”

“Can you—can you sit down?” asked Scrooge, looking doubtfully at him.

“I can.”

“Do it, then.”

The ghost sat down on the opposite side of the fireplace.

“You don’t believe in me,” observed the Ghost.

“I don’t,” said Scrooge.

“What evidence could I give you that would be stronger than that of your senses?”

“I don’t know,” said Scrooge.

“Why do you doubt your senses?”

“Because,” said Scrooge, “the senses are easily affected by small things. For example, a slight stomachache could make me see something strange. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a piece of an undercooked potato. I don’t know if you are from the grave or from the gravy!”

Scrooge didn’t usually crack jokes like this, and he wasn’t feeling particularly comedic at that moment. The truth is that he was trying to be smart as a way to distract himself and keep down his terror. The ghost’s voice disturbed him down to the marrow of his bones.

The ghost sat, staring at Scrooge with those fixed eyes in silence. It was perfectly motionless, except for its hair and tassels, which seemed moved as if affected by the hot vapor from an oven.

“You see this toothpick?” said Scrooge, pointing. He wished, even for just a moment, for the ghost to divert its stony gaze.

“I do,” replied the Ghost.

“You are not looking at it,” said Scrooge.

“But I see it,” said the Ghost.

“Well!” returned Scrooge, “I might as well swallow it and torture myself. Humbug, I tell you! humbug!”

At this, the spirit raised a frightful cry, and shook its chain with such an appalling noise, that Scrooge held on tight to his chair, to save himself from fainting. But his horror was greater when the phantom took off the bandage around its head, as if it were too warm to wear indoors, and its lower jaw dropped down on its chest!

Scrooge fell to his knees, and clasped his hands in front of his face.

“Mercy!” he said. “Dreadful ghost, why do you trouble me?”

“Man of the worldly mind!” replied the ghost, “do you believe in me or not?”

“I do,” said Scrooge. “I must. But why do spirits walk the earth, and why do they come to me?”

“It is required of every man,” the ghost said, “that the spirit within him walk among his fellow men, and travel far and wide. And if that spirit doesn’t go forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world. Oh, woe is me! I am condemned to walk the earth after death. I can witness but I cannot share it. I might have been able to truly experience it while I was still alive and been happy!”

Again the ghost cried out, and shook its chain in its shadowy hands.

“You are in chains,” said Scrooge, trembling. “Tell me why.”

“I wear the chain that I forged in life,” replied the ghost. “I made it link by link, and inch by inch. I made it with my own free will. And of my own free will, I wear it. Is it strange to you?”

Scrooge trembled more and more.

“Don’t you know,” continued the ghost, “the weight and the length of the strong coil that you wear yourself? Seven Christmas Eves ago, it was as heavy and as long as this one. You have continued laboring on it, since. It is a cumbersome chain!”

Scrooge glanced around him on the floor, in the expectation of finding himself surrounded by some fifty or sixty chains of iron cable, but he could see nothing.

“Jacob,” he said, imploringly. “Old Jacob Marley, tell me more. Tell me something good, Jacob!”

“I have nothing good to say,” the Ghost replied. “I cannot rest. I cannot stay. I cannot linger anywhere. My spirit never walked beyond our office. In life, my spirit never went beyond the narrow limits of our money loaning business. And weary journeys lie ahead of me!”

It was Scrooge’s habit, whenever he became thoughtful, to put his hands in his pockets. Pondering on what the ghost had said, he did so now, but without lifting up his eyes, or getting off his knees.

“You must have been very slow about it, Jacob,” Scrooge observed, in a business-like manner, though with humility and deference.

“Slow!” the ghost repeated.

“You’ve been dead for seven years,” mused Scrooge. “And traveling the whole time!”

“The whole time,” said the ghost. “No rest, no peace. Incessant torture of remorse.”

“You travel fast?” said Scrooge.

“On the wings of the wind,” replied the ghost.

“You should have traveled a great distance in seven years,” said Scrooge.

The Ghost, on hearing this, cried again, and clanked its chain so hideously in the dead silence of the night.

“Oh! Captive, bound, and double-ironed,” cried the phantom, “You don’t know. The passing of time is different for immortal creatures. Any Christian spirit will find its mortal life too short to be of any use. But after death, no amount of time can make amends for a misused life. I misused my life! Oh, how I misused my life!”

“But you were always a good business man, Jacob,” said Scrooge.

“Business!” cried the ghost, wringing its hands. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business. Charity, mercy, tolerance, and kindness were all my business. The dealings of my trade were only a drop of water in the ocean of my business!”

It help up its chain at arm’s length, as if that were the cause of all its grief, and flung it heavily on the ground again.

“At this time of the year,” the ghost said, “I suffer the most. When I was alive, why did I walk through crowds of fellow human beings with my eyes down? Why didn’t I ever raise my eyes to the North Start that led the Wise Men through the night?”

Scrooge was very dismayed to hear the ghost talking like this, and began shaking.

“Listen to me!” cried the ghost. “My time is nearly gone.”

“I will,” said Scrooge. “But don’t be hard upon me, Jacob! Please!”

“I don’t know why I appear before you now in a shape that you can see. I have sat invisible beside you for many, many days.”

That was not a pleasant thought for Scrooge. He shivered and wiped sweat from his forehead.

“I am here tonight,” continued the ghost, “to warn you that you have a chance of escaping my fate. I have procured that chance for you, Ebenezer.”

“You were always a good friend to me,” said Scrooge. “Thank you!”

“You will be haunted,” resumed the ghost, “by Three Spirits.”

Scrooge’s face fell almost as low as the ghost’s jaw had done.

“Is that the chance you mentioned, Jacob?” he demanded, in a faltering voice.

“It is.”

“I—I think I’d rather not,” said Scrooge.

“Without their visits,” said the ghost, “you cannot hope to avoid the path I walk. Expect the first tomorrow, when the clock strikes One.”

“Couldn’t I see them all at once, and get it over with quickly, Jacob?” hinted Scrooge.

“Expect the second on the next night at the same hour. The third on the next night when the last stroke of Twelve has ceased to vibrate. Don’t look for me anymore. I hope that, for your own sake, you remember what has passed between us!”

After it said those words, the phantom took its bandages from the table, and bound its head, as before.

By the sound of its teeth, Scrooge knew that the jaws were brought together by the bandage. He ventured to raise his eyes to look at the ghost again. It was standing in front of him, with its chain wound over and around its arm.

The apparition walked backward away from him. At every step it took, the window raised itself a little. By the time the ghost reached it, it was wide open.

It beckoned Scrooge to approach, which he did. When they were within two steps of each other, Marley’s ghost help up its hand, warning him not to come closer. Scrooge stopped.

He didn’t stop in obedience, but rather in surprise and fear, because when the ghost raised its hand, Scrooge became aware of the confused noises in the air. There were incoherent sounds of grief and regret. There were wailings of inexpressible sorrow. The ghost, after listening for a moment, joined in the mournful cries, and it floated out into the bleak, dark night.

Scrooge followed to the window, desperate in his curiosity. He looked out.

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering here and there in a restless haste, moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s ghost. Some of them were linked together. None of them were free. Scrooge recognized some of them as people he had met during his lifetime. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried out to his wife and child. All of the ghosts were in misery, wishing to go back to their lives on earth.

Whether these creatures faded into the mist, or the mist enshrouded them, he could not tell. But they and their spirit voices faded, and the night returned to normal.

Scrooge closed the window and examined the door that the ghost had entered. It was double locked, as he had locked it with his own hands, and the bolts were undisturbed. He tried to say “Humbug!” but stopped at the first syllable. From the emotion that he had undergone, or the fatigue of working, or his glimpse of the Invisible World, or the dull conversation of the ghost, or the lateness of the night, he felt very tired. He went straight to bed, without even undressing, and fell asleep instantly.

One thought on “A Christmas Carol – Marley’s Ghost – Chapter 1”